Sharing is caring

news to use

You read - you know...

fresh from the press

the feed to read

A newspaper, not a snooze paper

Workshops in Hamburg & Wetzlar

Workshops and a lecture about multilayer photography with Leica

NY Photography Awards Winner

I won 2x Gold and 8x Silver at the New York Photography Awards 2024!

CU at the YEAST photography festival

Exhibition “CŪ” at the YEAST photo festival, Italy.

Exhibition Leica Gallery Duesseldorf

Exhibition “Ansichtssache Duesseldorf” in the Leica Gallery Duesseldorf.

LEICA Camera Blog

November 2, 2020

My series SAMSA is featured in the Leica Camera Blog, thanks to the Leica Team!

Along with some pictures from the series you can read an interview about it.

Here you can read an excerpt of the interview, the whole text is available on the Leica Gallery page.

It’s always nice to talk to interested people about your work…

Here is a part from the interview:

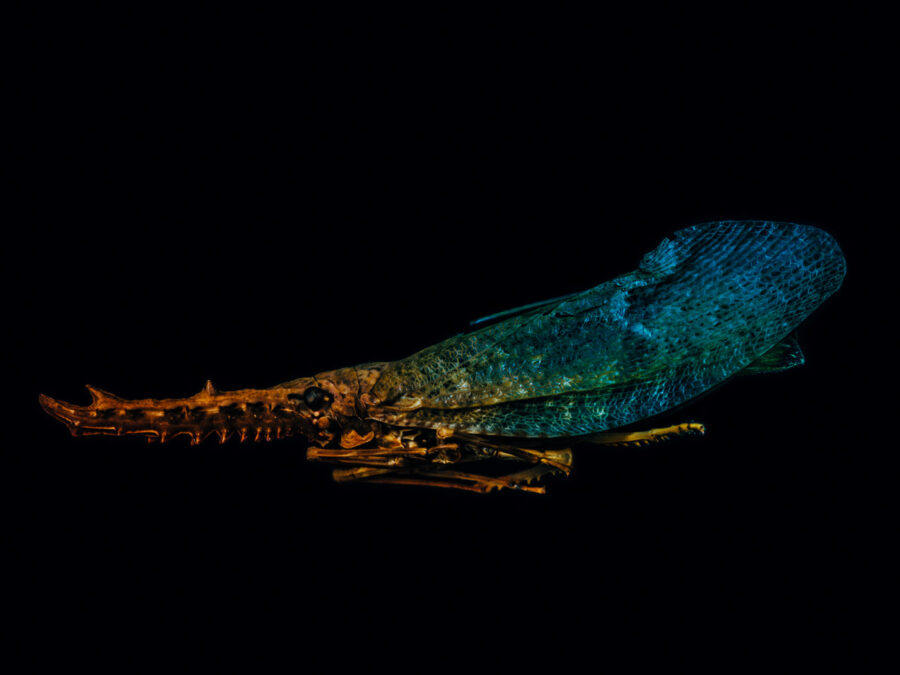

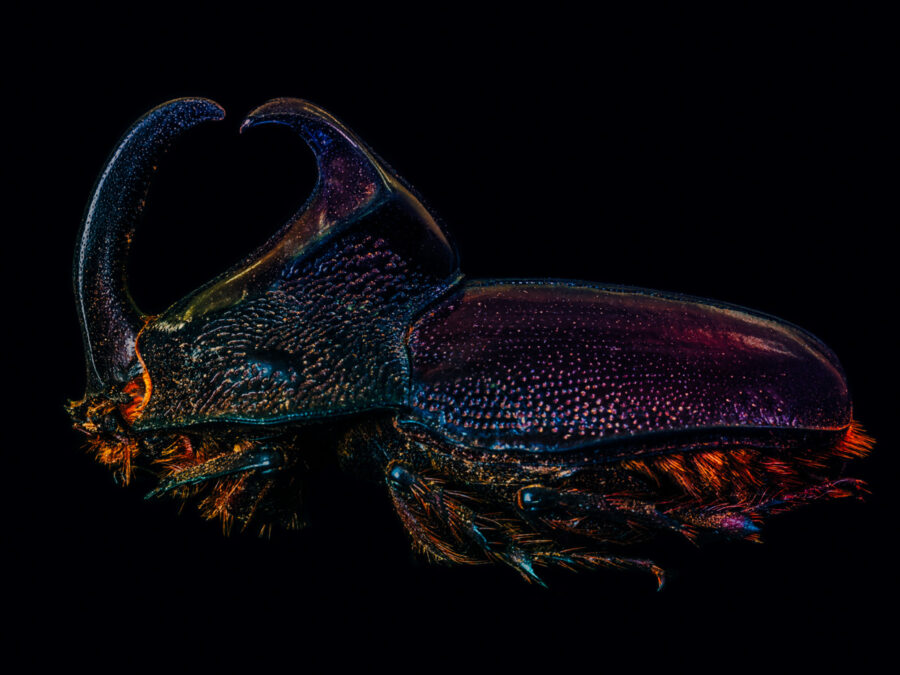

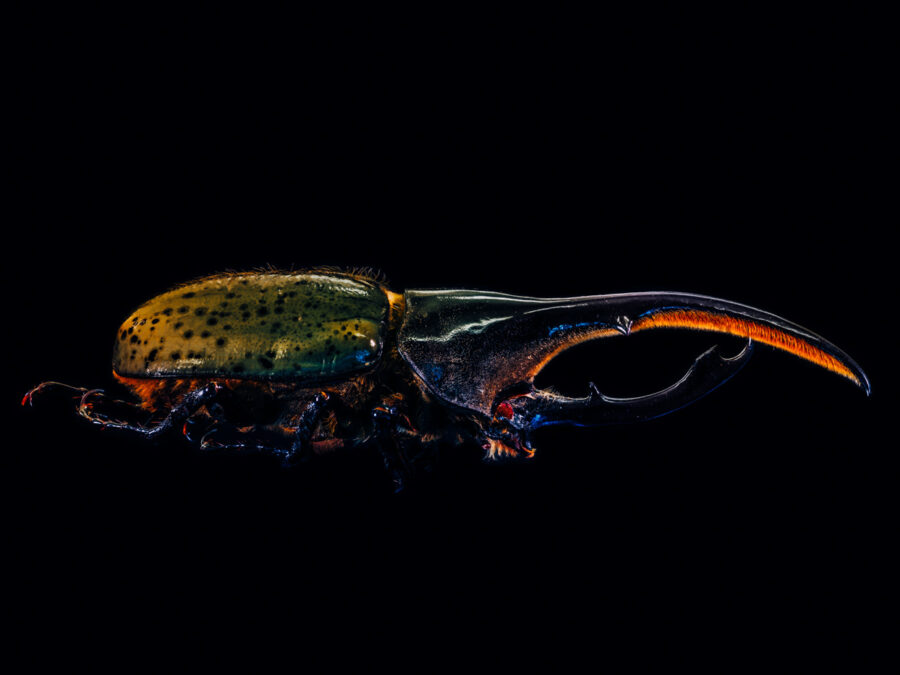

Using tweezers, gloves and a Leica SL2, Florian W. Müller staged tiny insects in very large settings. The outcome is psychedelic and technically-perfect images that shine a very different light on macro photography.

What photography genre did you work in originally? What does your photographic work normally look like?

My work as an artistic photographer is defined significantly by shapes and abstract compositions, such as multiple exposures or disassociations. In the broadest sense, I do a lot of still life and object photography; but also architecture and landscape. As a commercial or commissioned photographer, I often have people in front of my lens, whether for portraits or company presentations; also cars. In this case, I’m very lucky because, as a result of my artistic work, I’m often given free rein and can even use artistic techniques. For example, for Porsche China I used triple exposures of the car, staging it in different urban settings.

What inspired you to use insects for a photo project?

I’ve been fascinated by insects, since I was a child. My father was a great and knowledgeable friend of nature, and I got that from him. I find the insect world a small and bizarre, but also beautiful, world; one which opens up to you, if you just take a closer look. I’ve been wanting to show this world for a long time; I began purchasing and photographing exhibits years ago. Over the long term, however, it was very cost-intensive, as I didn’t want to keep the specimens – just photograph them.

How did you manage to get hold of the specimens?

Last year I enjoyed a pleasant collaboration with the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. Through that connection, I got in touch with the Senckenberg German Entomological Institute. The manager there quickly agreed to my request. I was also assigned a colleague, who was very helpful in locating the best specimens from amid the gigantic collection, and who was able to answer all my questions and support me. I was able to build up a little studio at the institute, and worked there for three very enjoyable days in total.

How exactly did you go about taking the pictures?

The little photo studio consisted of a home-made tabletop cove and two LED permanent lights. To ensure that the insects were touched as little as possible, and could float free, I built a kind of platform out of cork and a magnet system; so afterwards, I didn’t need to cut out virtually anything.

What role did post-processing play in this project? How was the iridescent effect created?

It was not an insignificant one. Beetles often have the greatest colours and shimmering effects. However, this brilliance fades over the years; it becomes somewhat duller. I added some colours in post-production, frequently to emphasize the original colours; but also at times to achieve a certain effect that you don’t find in that form in nature. This always leads to entertaining conversations about the picture.

Is there a message behind the project, or should it just be appreciated at the technical level?

In fact, I’d like the technical refinement relegated to the background: it’s there, it’s the foundation of these photos, but it’s also an elegant understatement. Quite in line with Leica, the technical perfection of the pictures is a simple fact. I would like the viewer to focus on the objects – to be fascinated and curious, and then to see a beetle outside in the garden from another perspective. I’m happy if the pictures stir up emotions, because that’s fundamentally necessary, if you want to deal with something more than superficially. I don’t care if the emotion is disgust at first; the normal thing is then to look more closely and discover details that are normally hidden: “Oh, that’s the eye?” is something I often hear, for example. There is one clear aspect to the work: the fact that insects die is real. This is the unfortunate starting point for a whole chain of human-induced imbalances in nature. There is no big lobbying for insects; many consider them just small and a nuisance. I want to show their many facets (not only those in their eyes), how bizarrely beautiful they can be, and that it’s worth preserving them. It’s not only worth doing, it’s indispensable for a healthy balance in nature.

You’re pushing against the boundaries of photography with this project, and you enjoy experimenting in general. Do you think there are still plenty of new discoveries to be made in the field of photography?

There will always be new things that are worth discovering. The world continues turning, no day is like another, and technical progress (or the combination of old and new techniques) repeatedly allows space for new perceptions and insights in the most diverse directions. We are far from having seen everything, and much less from having photographed everything.

Interview: LFI Online Team